Too Small to Not Fail

A Short History of the World — Danielle DiMartino Booth

Dear Free Feather Subscribers,

Our QI Pro clients agree that releasing this recent publication to a wider audience is for the greater good and we dedicate this Weekly Quill to “every hardworking American who wakes up in the morning asking themselves what went wrong.” Please enjoy and consider upgrading to a paid subscription to The Daily Feather.

Sincerely,

Danielle

“It is worth noting that ‘too big to fail’ is not simply about size. A big institution is ‘too big’ when there is an expectation that government will do whatever it takes to rescue that institution from failure, thus bestowing an effective risk premium subsidy. Reforms to end ‘too big to fail’ must address the causes of this expectation.”

Jerome Powell, March 4, 2013

There was a time when there was honor among central bankers. That ended in August 2007, a century after J.P. Morgan envisioned a central bank of the United States that could staunch the bleed in times of financial crises. In an empty conference room at the Federal Reserve’s annual Jackson Hole Symposium, Ben Bernanke secretly met with a coterie of his closest confidantes to blueprint the response to a breakdown in the financial system. That day, in what few dare reference as the ‘Bernanke Doctrine,’ the precondition of taking interest rates to the zero bound before launching large-scale asset purchases was decided.

Not present were Thomas Hoenig, Charles Plosser and Richard Fisher, members of the Federal Open Market Committee who would have, no doubt, vociferously objected to the presumption of zero interest rate policy, or ‘ZIRP,’ as it’s known. Such reckless policy would surely encourage speculation and malinvestment of the worst kind. What’s worse, it would be exceedingly difficult for the bank to extricate itself from the policy. These arguments were never considered. Those who would have defended the nation’s long-term prosperity were never invited.

When the inevitable catastrophe did erupt, winners and losers were chosen. Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers were targeted to fail. By the virtue of the Troubled Asset Relief Program, which soaked up the same bad assets that sank the Chosen Two, Citigroup was saved from suffering the same fate. The big bank was deemed, “Too Big to Fail.”

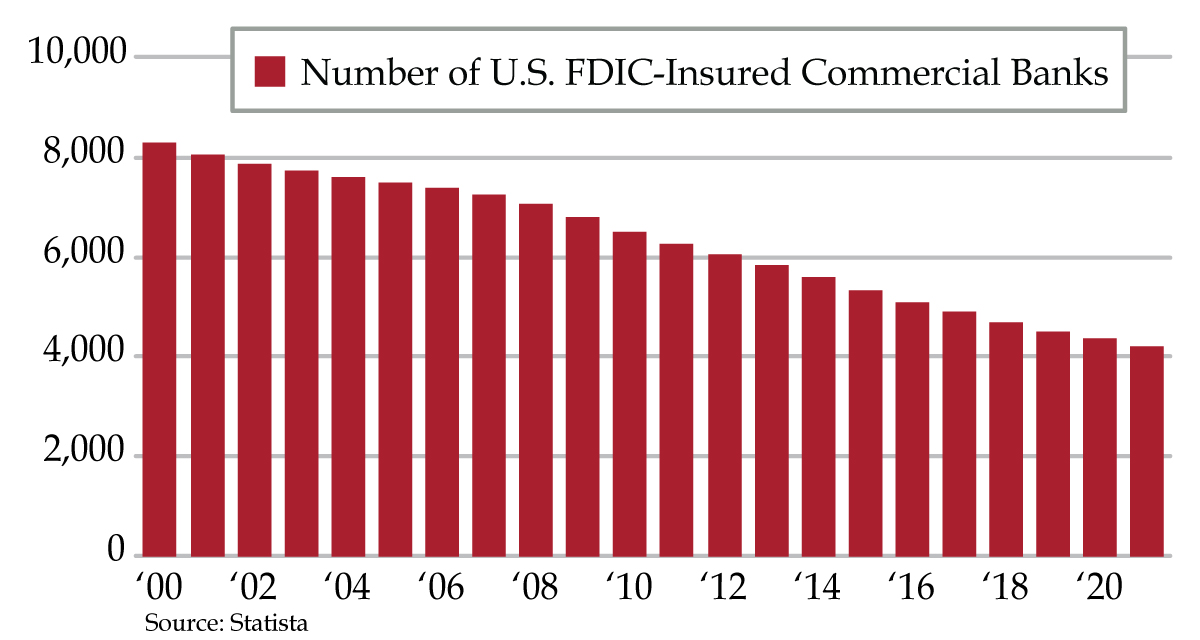

Brokered bank acquisitions in the heat of the crisis made the biggest banks bigger. And the Fed’s Large Scale Asset Purchase program, what we refer to as Quantitative Easing, further enriched these mammoths. The passage of the Dodd-Frank law, designed to eradicate Too Big to Fail (TBTF), instead indemnified it. On July 15, 2015, the five-year anniversary of Obama’s signing the bill into law, then Texas Congressman Jeb Hensarling, wrote an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal: “The statute itself declared that it would ‘end too big to fail’ and ‘promote financial stability.’ None of that has come to pass. Too-big-to-fail institutions have not disappeared. Big banks are bigger, small banks are fewer, and the financial system is less stable.”

When I was at the Dallas Fed, I had the good fortune to visit Hensarling and discuss TBTF. I had attended a board meeting at the 12th District’s San Antonio branch and was saddened to hear of community banks’ struggles with overbearing costs of complying with Dodd-Frank, which required banks with $10 billion or more in assets to be stress-tested annually. The onboarding of staff to comply was pure overhead. To the alarm of the regulators in attendance that day, to defray the added costs, some of the banks were making commercial real estate loans at ridiculous rates. Other banks were simply closing their doors. As Hensarling wrote, “Dodd-Frank was supposedly aimed at Wall Street, but it hit Main Street hard. Community financial institutions, which make the bulk of small business loans, are overwhelmed by the law’s complexity. Government figures indicate that the country is losing on average one community bank or credit union a day.”

The Demise of U.S. Community Banking

By the time the rules were relaxed in 2019, it was too late. The damage to loan books had been done. And the number of community banks had been decimated.

That same year also kicked off with the Powell Pivot. Jerome Powell’s first year in office, 2018, was not enviable. Resolute to break politicians’ and Wall Street’s grip on monetary policy, he launched a double tightening campaign – raising interest rates and shrinking the Fed’s balance sheet at the same time. Quantitative Tightening was also a global phenomenon, one that sent risky assets into coordinated selloff. For a time, Powell held his ground. But the pressure proved too much.

On January 4, 2019, Jerome Powell publicly apologized for castigating QE in his early years on the Federal Reserve when he campaigned against ZIRP and QE. It was a classic, “I was young, and I needed the money” explanation. After a record 41 days without one single high-yield bond sale infecting the stock market, culminating in the Christmas Eve of 2018 blood bath, the Street came roaring back. Overnight, Powell went from being public markets’ enemy No. 1 to its hero.

While not inside the room, I can only imagine what brought on the about-face. There must have been a string of panicked phone calls Powell had with Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda. A December 2019 report released by the Basel-based Financial Stability Board noted that “Banks’ direct exposure to third-party CLOs totaled US$207 billion, or 28% of CLOs outstanding, as of end-2018. The largest portion was held by Japanese banks ($107 billion) and U.S. banks ($85 billion).”

By then, Japanese regulators had directed banks with as much as 40% of their assets in these collateralized loan obligations to diversify away from these high-risk holdings. But the damage had been done. While I harbor no sympathy for what followed, the biggest victim was Powell himself. His reputation has never recovered. He’d seen the whites of the eyes of global systemic risk emanating from the hyper-levered U.S. corporate debt markets and saw no choice other than standing down.

What followed was the Street doubling down, piling ever more leverage onto Corporate America’s balance sheet. As risky assets became riskier yet, the tension in the financial system became untenable. The cessation of QT proved to be too small a dose of heroin for the drug addict that is the Street. A feeble attempt at “Not QE” bought some time. But stop gaps eventually must be replaced by permanent solutions. Rescued by a global pandemic, Powell was able to make ZIRP and QE great again.

The unforeseen was the upshot of extricating the banking system from the credit allocation process. Monetizing 43.2% of U.S. GDP, a product of Trump, the U.S. Congress and Biden one-upping each other to pass record stimulus measures, created the mother of all inflationary spirals. Deluged by deposits, Powell’s vow to hold the zero bound amidst “transitory” inflation prompted banks to follow the Fed into securities purchases. QE for everyone!

The kicker was Biden’s mission to set the nation on a path to a welfare state, resplendent with sufficient social spending to annihilate the American work ethic. The backbiting that ensued as the Administration tried, and failed, to replace Powell with Lael Brainard, was the coup de gras. Of course, the markets wanted none of the future envisioned by Brainard. The lobbying community came out in full force against her nomination. As it became apparent that Biden was holding Powell’s renomination hostage to get the consolation prize of political, progressive appointees to the Fed Board, a leadership vacuum paralyzed policymaking. The Fed staff divided, “transitory” languished, making Powell look all the more the fool.

By the time Powell’s vote was finally allowed to come to the Senate, garnering a resounding 80 Senate votes to Brainard’s 52 for Vice Chair, the man was emasculated, his character shredded.

I pause here to ask one simple question: What would you have done in his shoes?

Did banks follow Powell hand-over-foot into Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities? We know they did. They had little choice. You can clearly see on the charts the spike in the trajectory of these holdings after the pandemic flash recession.

Bank Holdings Up. Bank Holdings Down.

Powell didn’t just find himself “behind the curve.” He was faced with an existential question. Could the cycle be broken? Could the Fed Put ever be retired into the annals of policy errors? Powell made the choice to try to break the cycle. He knew he would break something.

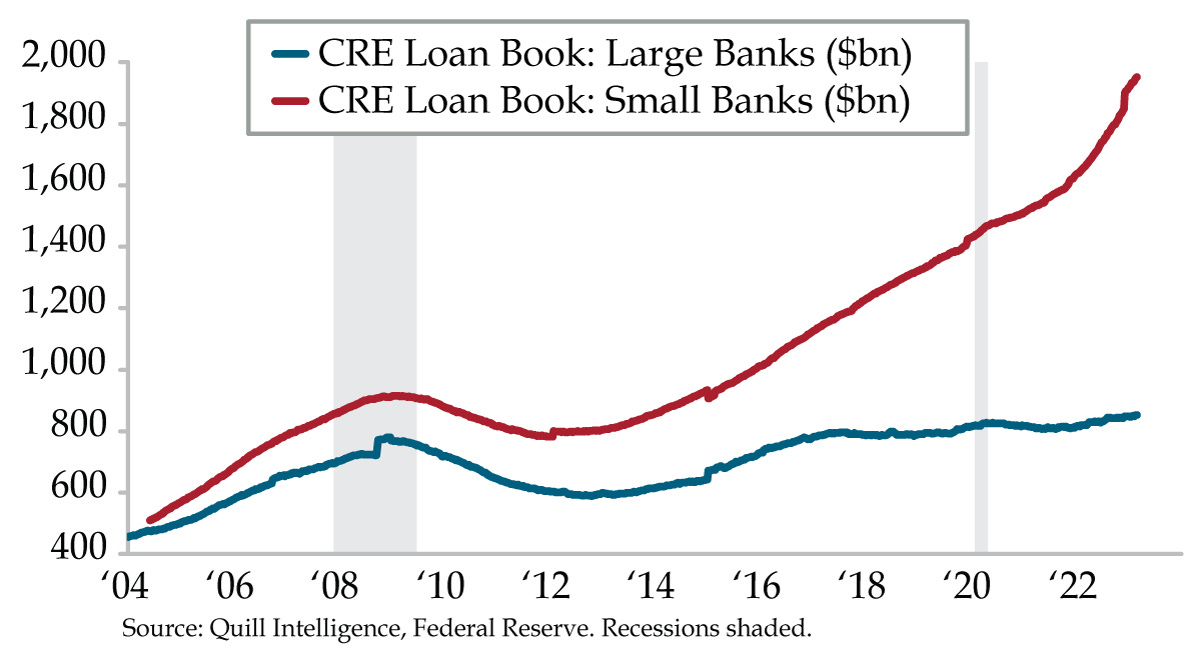

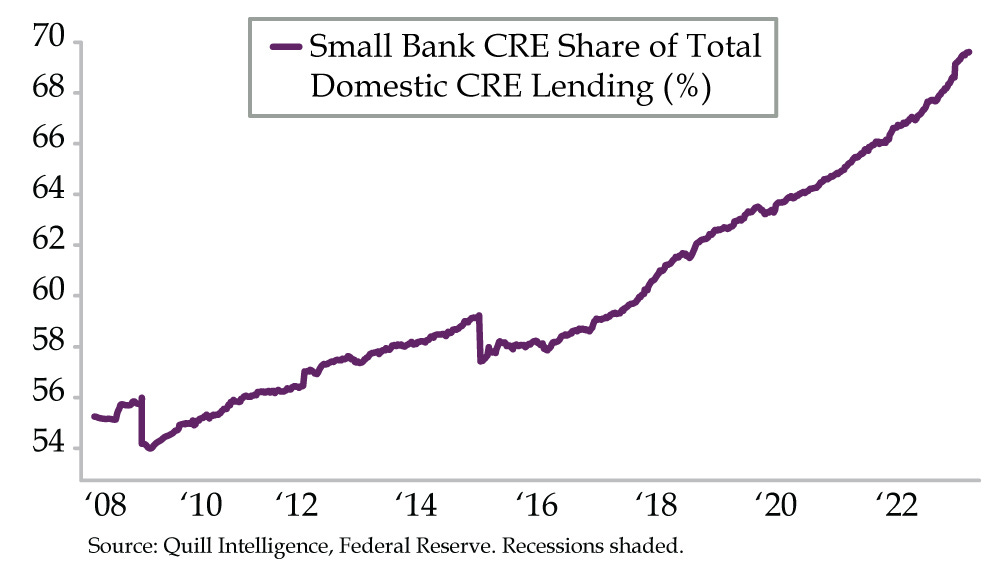

Back in October, QI friend Patrick Perret-Green of PPG Macro warned that what would eventually break was small banks. The London-based strategist has had his eye on the same building risk as that of former Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren – commercial real estate concentration. As Perret-Green explained, “When it comes to commercial and industrial and consumer lending, (small banks”) share is largely in line with the 30% total asset share (of the 25 largest banks). Real estate is the nasty. In that latest data, the total amount of real estate lending was $5.061 trillion. The exposure of the big 25 was only $2.351 trillion. The small bank sector was on the hook for $2.693 trillion: 53.2% of all bank real estate lending. Unfortunately, the situation is much, much worse. Within the total real estate lending number, commercial real estate (CRE) amounts to $2.631 trillion. Small banks are responsible for a record 68.9% share of CRE lending: 1.806 trillion of it.”

The numbers Perret-Green references are time-stamped from last October. We’ve updated the graph illustrating the growing disconnect between large and small banks in the CRE space.

Small Banks Immerse Loan Books in Commercial Real Estate

You may be asking why I’ve run off on a tangent about credit risk when the current banking crisis is one grounded in interest rate risk. Despite what’s transpired in the regional banking space, Powell is not going to “break” the sector. To truly break something, you need the added ingredient of credit risk, which will come to the fore in expedited fashion as a result of interest rate risk. As you can see, the crisis of confidence has been even more damaging to small banks, which stands to reason for shocked U.S. households scrambling to the security of the biggest banks or yield on offer by money market funds.

The bottom line is the less liquidity small banks have, the more at risk their illiquid assets. If the deposit hemorrhaging and recession don’t kill them first, Yellen selling hundreds of billions of Treasury Bills at prevailing rates once the debt ceiling is resolved surely will.

Small Bank Deposit Run Deeper than that of Large Banks

In an interview with the Financial Times on Monday, Tom Michaud, CEO of Keefe, Bruyette & Woods, did a great job of explaining the higher risk of runs at smaller banks. As the FT pointed out, “The specialist investment bank has had a helpful vantage point; its analysts focus on less heavily covered parts of the financial sector.”

I’m going to make a leap of faith that, at this point, you’re familiar with the terms hold-to-maturity losses and uninsured deposits. Since last Friday, every financial publication on the planet has described them ad nauseam. With that, you’ll appreciate the succinct manner in which Michaud explains the risk to the broader banking system and smaller banks in particular:

“These underwater bond positions are going to have to be addressed. That’s what the market has decided it wants to focus on. Banks who have larger [mark-to-market losses] could be candidates to raise capital. But I also don’t think that their position is as dire as Silicon Valley’s. Remember it was an outlier, and its bond portfolio was so much bigger than a typical bank’s that it was an unusual circumstance…but no typical bank has anything to the degree of Silicon Valley Bank. That’s why we need orderliness, so it can get straightened out. Most owners of bonds — whether you’re a bank or not — have a loss in your bond portfolio. Interest rates are higher, so that shouldn’t be a shocker to anybody. But depositors are going to test the strength of the system, and that’s what’s happening now. And banks with bond losses that are not significant may still get tested because the market is nervous. That’s why we need the government, banking agencies, here to calm things down. The real issue is confidence in uninsured deposits. There are some really strong banks out there that may see some deposit outflows because of loss of confidence. It makes a key metric, the size of your bank, the key metric.”

After being asked over the weekend by mentor Arthur Cashin, I have a better understanding of the magnitude of uninsured deposits at U.S. banks. As of the fourth quarter, per the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), U.S. banks were sitting on $17.7 trillion in deposits. Of that total, 51%, or $9.0 trillion, was uninsured.

Uninsured Deposits Comprise More than Half of U.S. Bank Deposits

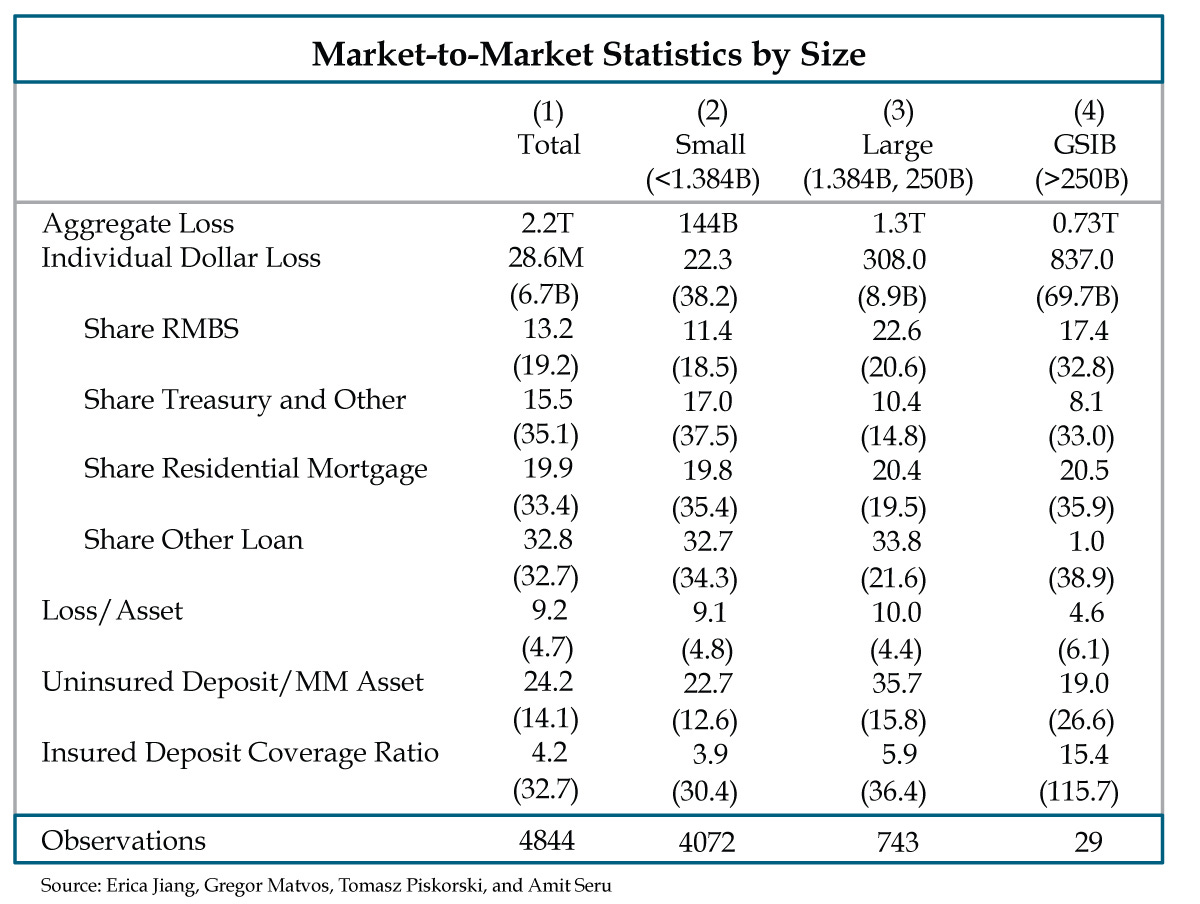

A separate FT article yesterday brought to my attention something remarkable – a timely academic paper on the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) debacle published Monday by Erica Jiang, Gregor Matvos, Tomasz Piskorski, and Amit Seru. The conclusion is that as of this year’s first quarter, U.S. banks in the aggregate are sitting on $2.2 trillion in unrecognized losses. Moreover, there are a good number of banks with worse capital positions vis-à-vis SVB. The origin of the losses depends on the size of the bank. For Globally Systematically Important Banks, the biggest losses are tied to residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS). In the case of small banks, losses are most concentrated in “Other Loans.”

At the risk of causing a headache, it’s worth a moment to study the table that produced the $2.2 trillion figure. You can see that the Insured Deposit Coverage Ratio is the lowest for the smallest banks. For a full explanation of the findings, the paper details:

“This table presents the descriptive statistics of our key metrics after we find the mark-to-market asset values for each FDIC-insured depository institution in the U.S. Aggregate loss is the total dollar losses calculated by summing over all dollar losses at each bank based on their 2022Q1 balance sheets. All other numbers outside parentheses are sample median values. Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations. Dollar losses are defined in the main text. We decompose all losses into losses from RMBS, Treasury and other securities, loans secured by residential 1 to 4 family properties (residential mortgage), and other loans. These values are expressed in terms of the percentage of total losses in the table. Loss/Asset is the percentage loss of the asset book values as of 2022Q1 after market to market the main asset categories as described in the main text. Uninsured Deposit/MM Asset is the uninsured deposit amount as reported in 2022Q1 bank call reports divided by the mark-to-market asset value. Insured Deposit Coverage Ratio is defined as (mark-to-market asset value - uninsured deposit -insured deposit)/insured deposit.”

Small Banks Have the Lowest Insured Deposit Coverage Ratio

What grates the most upon reading the SVB entrails is the lobbying effort specifically on the part of its CEO, Greg Becker. It’s clear that small banks with $10 billion in assets should never have been subjected to the Fed’s stress tests. It’s equally plain that banks with between $100 to $250 billion in assets should never have been allowed to get off the hook. At the time, in 2015 SVB assets were approaching $50 billion. Under the law at the time, that would have triggered “enhanced prudential standards,” code for higher capital requirements and closer regulatory scrutiny. Dodd-Frank would have required a “living will” be submitted detailing how the bank would weather severe circumstances. If the will was not approved by the FDIC and the Fed, SVB would have had to restructure, raise capital, divest, or downsize. And what fun is that?

In a written statement to lawmakers, Becker made an argument better suited to a true small bank: “These new burdens and the related compliance costs and necessary management time and other human resources are significant, and will require us to divert resources and attention from making loans to small and growing businesses that are the job creation engines of our country, even though our risk profile would not change.” Because of “SVB’s deep understanding of the markets it serves, our strong risk management practices”, a $250 billion threshold was much more befitting the strong corporate citizen. The alternative if his lobbying failed: “Given the low risk profile of our activities and business model, such a result would stifle our ability to provide credit to our clients without any meaningful corresponding reduction in risk.”

As reported by The Guardian, “Two months later, SVB added the former Obama Treasury Department official Mary Miller to its board, noting she had previously helped oversee ‘financial regulatory reforms.’” Becker sold $3.6 million in SVB stock 12 days before it went under.

In the case of SVB, as it bled deposits, a fire sale of “available-for-sale” (AFS) securities triggered a $1.8 billion loss that catalyzed its rapid demise. The subsequent inability to raise capital was the nail in its coffin.

In an outstanding MarketWatch op-ed, Philip van Doorn screened other banks with profiles that are similar to that of SVB in terms of the their exposure to unrealized AFS losses. He does this by pulling banks’ Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (AOCI) from bank filings. AOCI “Includes, but is not limited to, net unrealized holding gains (losses) on available-for-sale securities, accumulated net gains (losses) on cash flow hedges, cumulative foreign currency translation adjustments, and accumulated defined benefit pension and other postretirement plan adjustments.”

As van Doorn explained, “On the regulatory call reports, AOCI is added to regulatory capital. Since SVB’s AOCI was negative (because of its unrealized losses on AFS securities) as of Dec. 31, it lowered the company’s total equity capital. So a fair way to gauge the negative AOCI to the bank’s total equity capital would be to divide the negative AOCI by total equity capital less AOCI — effectively adding the unrealized losses back to total equity capital for the calculation.” Applying this methodology to U.S. banks with at least $10 billion in assets yielded the table below.

Banks Sitting on Untenable Levels of Unrealized Losses on “Available for Sale” Securities

Note that the second bank on the list has put itself up for sale as a double downgrade to junk and a massive run have left it with fatal injuries. I would add that van Doorn called out the nation’s biggest auto lender as being particularly at risk: “Ally Financial Inc. — the third largest bank on the list by Dec. 31 total assets — stands out as having the largest percentage of negative accumulated comprehensive income relative to total equity capital as of Dec. 31.”

The subject of a sector deeply reliant on funding outside the U.S. banking system brings us to the greatest menace that grew out of Dodd-Frank, one that’s deep in the realm of the unknown, in the bowels of the financial system. You likely caught the headline that Blackstone founder Stephen Schwarzman took down a cool $1.2 billion paycheck in 2022. Denying conventional banks from speculating with the house money (I paraphrase) set off a brain drain of Biblical proportions. As I often quote, the global nonbanking financial sector was $220 trillion as of the end of 2020; that compares to $180 trillion in the regulated conventional global banking sector.

How are we to have any inkling as to what the effect of high interest rates, illiquidity and a global recession is in a mammoth sector that regulators can’t even see? Private capital is exponentially more dependent on ZIRP. We’ve only just begun to see risk bubble to the surface in the lowest rated publicly traded credit. The default and bankruptcy cycles have barely started.

What is visible is the deep freeze securitization is entering, which poses an existential risk to the U.S. auto and commercial real estate markets. Three weeks ago, we published Driven to Extremes, a deep dive into the high-octane risk facing the U.S. hyper-leveraged, loss-riddled auto sector. Since then, we’ve seen an acceleration in the cancellation of auto-loan backed asset-backed securitizations pricings and one lender after another announce it is clamping down on lending standards. Heck, even Cox Automotive warned that income tax refund season has been a disappointment. The upheaval in the banking sector will only expedite the bursting of the auto lending bubble. Any notion that auto manufacturers can escape incentive spending is also moot. To that end, the stock of General Motors closed down today by 3.6%, more than double that of AutoNation, which closed down by 1.5%.

Collapsing banks inspired American Banker to publish an article asking, “Will Commercial Real Estate Loan Losses Be the Next Big Problem for Banks?”

Chris Marinac, the director of research at Janney Montgomery Scott, was interviewed for the article and cautioned that, “A lot of banks are going to have to step up disclosures about their office exposure. What are they really doing to stress test office loans, and what are they actually doing about problems?”

According to data provider IBISWorld, the delinquency rate in the $3 trillion Office sector rose to 17% in this year’s first quarter from 12% at the end of 2022, a level on par with that of the financial crisis. The article added that D.A. Davidson figures that when subleasing is included, total vacancy rates exceed 20%, twice the pre-pandemic rate.

A daunting punctuation on small banks’ relatively larger deposit drain was the compulsion with which they dove into lending into the $20 trillion CRE market. As the article forewarns, “Experts say the troubles amplified the risk-taking inherent in banking. With economists forecasting a recession this year amid stubborn inflation and lofty interest rates, analysts are also sharpening their collective focus on threats embedded in commercial real estate, given many small and midsize banks’ dependence on such lending, and they are homing in on the beleaguered office sector in particular.”

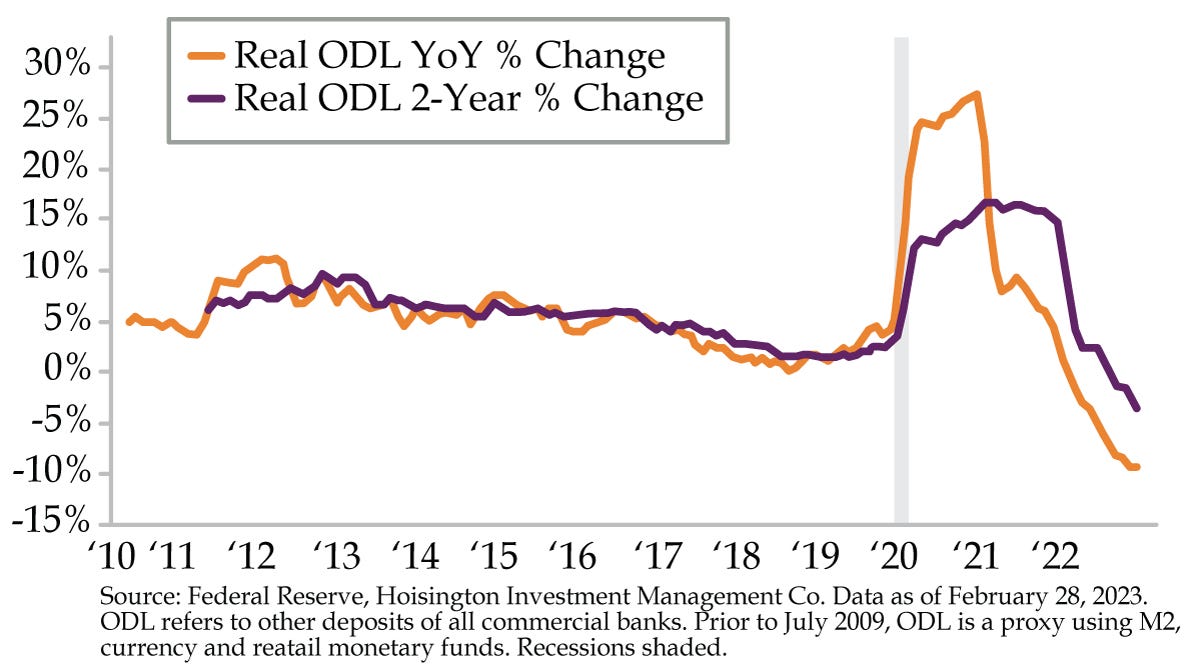

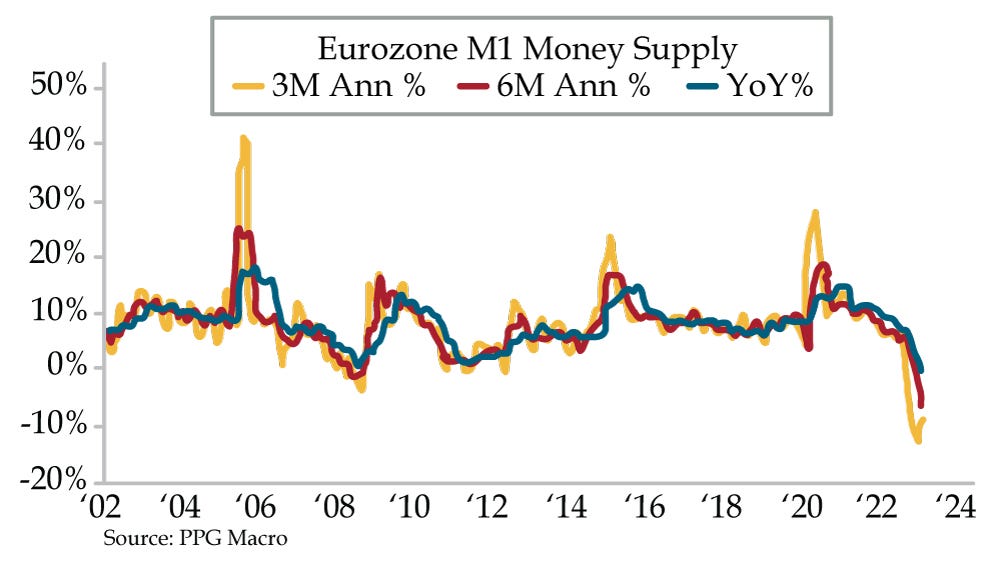

The seizure in nonbanking sector will only exacerbate the illiquidity plaguing CRE. If the collapse in the growth of monetary aggregates has been sufficient to instigate bank failures, it’s difficult to envision its effect on the less liquid nonbanking sector. With Credit Suisse in the spotlight, it’s notable that money growth is falling at a faster pace in Europe. Into this breach, Madame Lagarde is expected to raise the European Central Bank’s overnight rate by 50 basis points?

The Liquidity Starting Point for a Global Recession and Financial Crisis

And then there’s Powell’s Predicament. If systemic risk is not unleashed, which rate volatility at the highest since 2009 suggests is a big ‘if,’ what on earth does he do come next Wednesday? One perusal of Bloomberg headlines tells you the left-leaning financial media is relishing in crucifying Powell. Consider this gem that crossed the terminal this morning: “Powell’s Legacy Risks Being Tarnished Further by SVB Collapse.”

As a member of the Fourth Estate, I could almost feel the reporter’s enjoyment in penning, “His reputation was tarnished by his repeated insistence in 2021 that the surge in inflation then taking hold was ‘transitory.’ He then pivoted in the following year to overseeing the most aggressive monetary tightening campaign since the 1980s to try to rein prices back in. Those rapid-fire rate increases contributed to the problems at SVB, as its holdings of otherwise ultra-safe Treasury and agency bonds lost value.”

I pause once more to repose the question: What would you have done in Powell’s shoes?

Why bother accepting Biden’s insultingly delayed renomination with a net worth that exceeds $100 million? Why not return to the comfort of his Chevy Chase home, work as a consultant and rake in $250,000 per speaking gig for walking around money? If all Powell SHOULD do TODAY is slam the fed funds rate back to the zero bound, why on earth did he even bother trying to get it in positive territory in the first place?

The grave error in logic being committed by growing hordes of Powell detractors is presuming to think policy can EVER be normalized if the Fed Put is not slain once and for all. Accepting loss. Thanks to Bernanke’s hubris and behind-closed-doors covert policymaking, there’s no reason to even HAVE a central bank when accepting loss is all that will be asked of the Fed’s leadership. There is no policymaking required in leaving interest rates at the zero bound and the mechanics of buying every Treasury issued for the rest of time. Allow the Treasury to absorb the task of buying its own issuance and save the taxpayers the money of keeping the lights on at the Eccles Building. I’m sure U.S. politicians can contend with that pesky thing called hyperinflation while they kiss capitalism and the reserve currency status of the U.S. dollar goodbye.

In March 2013, Powell said in a seminal speech that he had entered a journey guided by the FDIC unconvinced that Too Big to Fail could be eradicated. Once he became familiar with the methodology, however, he relayed that he was pleased to have been swayed. He knew then and knows today that TBTF is a black eye on the U.S. financial sector. As he elegantly articulated:

“Under single point of entry, the FDIC will be appointed receiver of only the top-tier parent holding company of the failed financial group. Promptly after the parent holding company is placed into receivership, the FDIC will transfer the assets of the parent company (primarily its investments in subsidiaries) to a bridge holding company. Equity claims of the failed parent company’s shareholders will be wiped out, and claims of its unsecured debt holders will be written down as necessary to reflect any losses in the receivership that the shareholders cannot cover. To capitalize the bridge holding company and the operating subsidiaries, and to permit transfer of ownership and control of the bridge company back to private hands, the FDIC will exchange the remaining claims of unsecured creditors of the parent for equity and/or debt claims of the bridge company. If necessary, the FDIC would provide temporary liquidity to the bridge company until the ‘bail-in’ of the failed parent company’s creditors can be accomplished.

It is crucial to recognize how this approach addresses the problem of runs. Single point of entry is designed to focus losses on the shareholders and long-term debt holders of the failed parent and to produce a well-capitalized bridge holding company in place of the failed parent. The critical operating subsidiaries would be well-capitalized and would remain open for business. There would be much reduced incentives for creditors or customers of the operating subsidiaries to pull away, or for regulators to ring-fence or take other extraordinary measures. If the process can be fully worked out and understood by market participants, regulators, and the general public, it should work to resolve even the biggest institution without starting or accelerating a run, and without exposing taxpayers to loss.”

Instead of mass mobilizing against Powell as if he was the reincarnation of King Louis XVI, why not grow up? In the absence of a solution without consequences, he’s made an attempt to steer the economy into the first recession from which it has the slightest chance of exiting without the dead weight of zombie companies, without the corrupt practice of anointing Wall Street’s kingpins the de facto makers of monetary policy. A wise man once said, “There is no such thing as a free lunch.”

Damn right there’s not. Perhaps we accept the truth in this wisdom and, in doing so, the consequences of our actions.

Wow. Wow. That is a Perfect Bullseye! Thank You.