The Winton Car Hauler

Alexander Winton put the pack animal out of business. As was the case with all innovators of the era, the introduction of the internal combustion engine was a game changer for Winton. Insofar as the American industry is concerned, it started in 1893 in Springfield, Massachusetts when bicycle mechanics J. Frank and Charles Duryea designed the first operable gasoline, as opposed to steam-engine, automobile. In 1895, they won their first car race and sold their first car the next year. Inspired by the disruptive potential of “horseless carriages,” the Winton Motor Carriage Company was launched in Cleveland, selling its first 22 cars in 1898. What he did next proved immensely helpful to the 30 American manufacturers who’d joined the industry and produced 2,500 cars in 1899. The explosive growth in the coming decade that saw 485 companies enter the rush to manufacture cars would have been slowed if not for Winton’s next invention to satisfy his need to transport his products to his customers. His car hauler is credited as the first semi-trailer truck.

In the decade ended 1914, the number of trucks rumbling down U.S. roads expanded exponentially, from 700 to 25,000. Today, there are roughly 1.77 million trucks that are “for hire,” up 170,000 since the pandemic hit. Refuting the “driver shortage” narrative, rejection rates are on the rise. Think of this as the Quits Rate applied to trucking – the pace at which contracted carriers accept or reject a load to haul; a falling rejection rate indicates capacity is freeing up. As of the week ended Friday, the rejection rate had fallen to 12.96%; it fell six percentage points (pps) in March alone, and 15 pps off its post-pandemic highs. For context, the lowest it was in the immediate aftermath of Covid was 2.50%.

Spot rates per mile have also tumbled – they closed last week at $3.34/mile and have fallen 11.6% since peaking in January. The media’s frenzied coverage of supply constraints has catalyzed an unprecedented wave of new entrants. In February, new fleet registrations hit 20,166; at its prior August 2019 peak, 9,511 new registrants entered the market. The upshot for these inexperienced operators: They’ve never had to operate through a slowdown and bought their trucks and hired their drivers at the top of the market. FreightWaves CEO Craig Fuller issued a stark warning: “With falling spot rates, declining volumes, surging fuel prices and inflation across the board, it will get ugly, very quickly for many of these operators. Back in 2019, FreightWaves reporters wrote about trucking bankruptcies almost every day. I expect this will become reality for us once again.”

Though Fuller’s gotten a ton of flak for getting out in front of this fast-unfolding downturn, a less salacious headline than his expecting a “bloodbath” in trucking was equally notable. It would seem

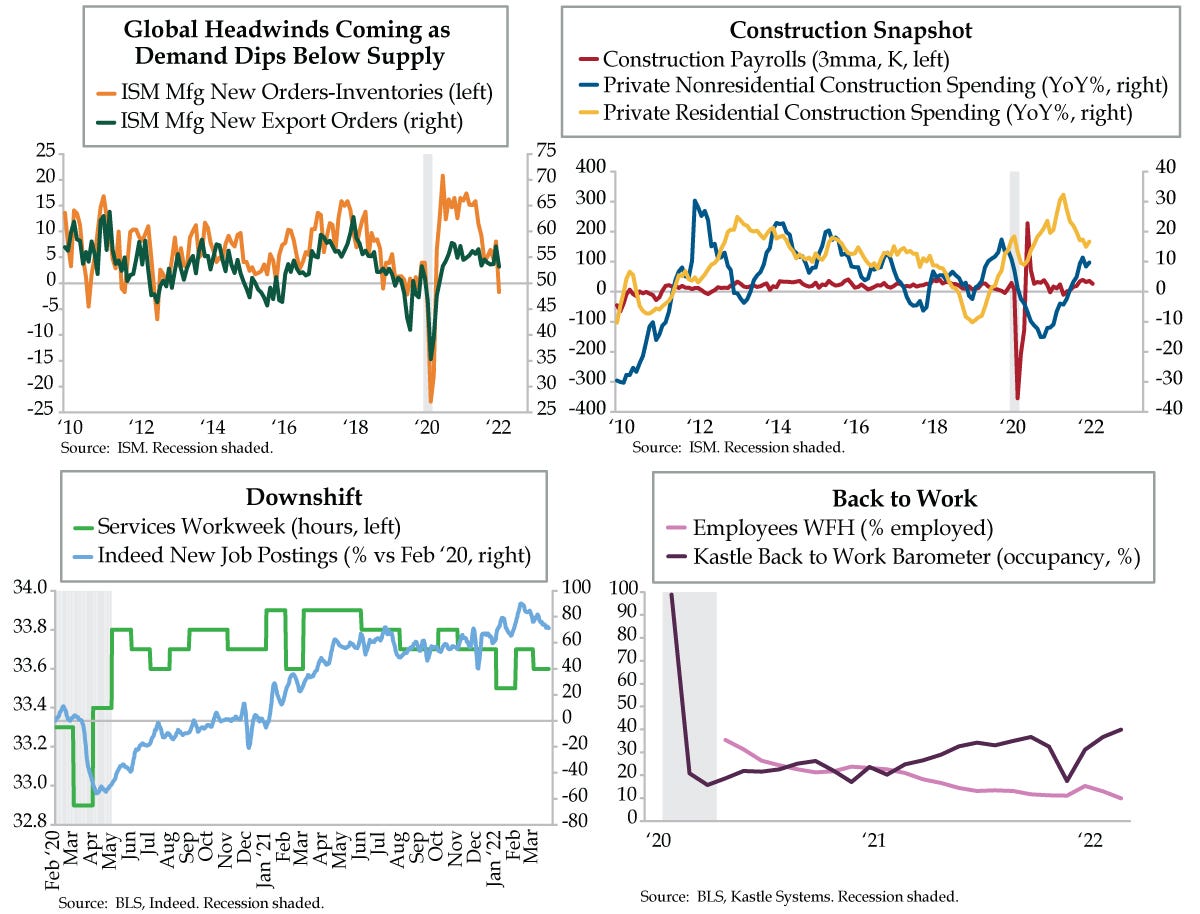

FedEx is slashing the base salaries of its estimated 300-500 internal sales workers to $38,000 from $50,000. As robust as the payroll figures were, the FedEx anecdote fits the hard data. Aside from January’s Omicron-driven smackdown, the U.S. service sector workweek (light green line) has largely tracked the growth of Indeed.com’s new job postings (light blue line), which peaked in early February.

Prisms into other areas of the economy validate Fuller’s observation that, “After two years of massive consumption of physical goods, consumers are pausing their spending.” ISM’s March reading showed supply fell underneath demand, as Inventories eclipsed New Orders (orange line) for the first time since May 2020. New Export Orders (green line) also slumped, falling to a near two-year low. Inflation is clearly biting around the world. On Sunday alone, Bloomberg ran with stories on Peru pushing up its minimum wage, the Sri Lankan government nearly dissolving and Indian manufacturers’ being choked by rising input costs – all tied to a global economy ravaged by inflation.

The U.S. Construction looks to be increasingly vulnerable as well. After gapping out to as much as 35 pps of a growth rate gap, nonresidential and residential construction’s growth rates (blue and yellow lines, respectively) have largely converged to their pre-pandemic levels. Normalization has also occurred in construction payrolls; its hiring nosedives and spikes abated in September 2020, when the 3-month moving average settled to 26,000. Notably, the post-pandemic rate of hiring peaked at 40,000 last December and has since fallen back to 27,000.

In what is another sign of life getting back to its old normal, at 9.99%, the percentage of employees working from home (purple line) slipped under 10% for the first time since the virus swept in on U.S. shores, less than a third of its May 2020 rate which was north of 35%. As for how much we can expect vacant offices to fill, with Kastle’s Back to Work barometer (pink line) rounding up to a post-pandemic high of 40% in March, February’s job layoffs data hint at permanent damage in occupancy. Not only were the biggest Quits Rate declines in Real Estate (-0.5%) and Finance (0.4%), at 0.3 pps, the largest increase in layoffs in February were in Professional & Business Services.

Fuller queried freight carriers to get a sense for how the on-the-ground reconnaissance squared with the rapidly deteriorating data. According to executive commanding a fleet of more than 1,000 trucks, “We were turning down 4 loads for every truck a year ago. Today, we are barely keeping our trucks running.” The cycle compression continues unabated.