The Daily Feather — Shocking

Dana: Tell me what this is.

Venkman: Lines. Two…no, three…wavy lines.

Dana: It’s amazing.

Venkman: You’re amazing with your ability to flood my psychic powers.

Dana: I can’t believe you used to shock your students.

Venkman: Between us, I only zapped the guys. [Dana, zaps Venkman]

Venkman: Well, that’s science. I know that now. I admit that.

Dana: Ready. Try this one. Take a moment.

Venkman: Uh…It’s a five-pointed star. Yes?

Dana: How are you doing that?

Venkman: Some believe that true love imbues the subject with the ability…[Dana, zaps Venkman]

Dana: Did you mark the cards?

Venkman: No.

Dana: You did, didn’t you?

Venkman: Yeah. [Dana, zaps Venkman]

Dana: It works well.

End-credit scenes rock. This one from 2021’s Ghostbusters: Afterlife pitted Dana Barrett (Sigourney Weaver) opposite Peter Venkman (Bill Murray) reprising a scene from 1984’s Ghostbusters. In the original, Venkman was the shocker. Thirty-seven years later, Venkman was the shockee. Note: It was the only scene that Weaver performed in the movie that paid tribute to the late Harold Ramis.

Economic data are also susceptible to extreme moves such as oil’s doubling from $20 to $40 s barrel after Iraq invaded Kuwait and early summer 2013’s “taper tantrum” which saw mortgage rates spike more than 100 basis points in eight weeks. Last Friday’s jobs report shocked on another level.

The trifecta of big beats for nonfarm payrolls and the average workweek coupled with a surprise drop in the unemployment rate generated a momentum trade in the rates market that followed through from Friday trading into Monday’s session. The yield curve bear flattened while expectations for second-quarter Fed rate hikes rose materially sending probabilities of quarter-point hikes at the May and June meetings from 40% and 7% to 80% and 42%, respectively.

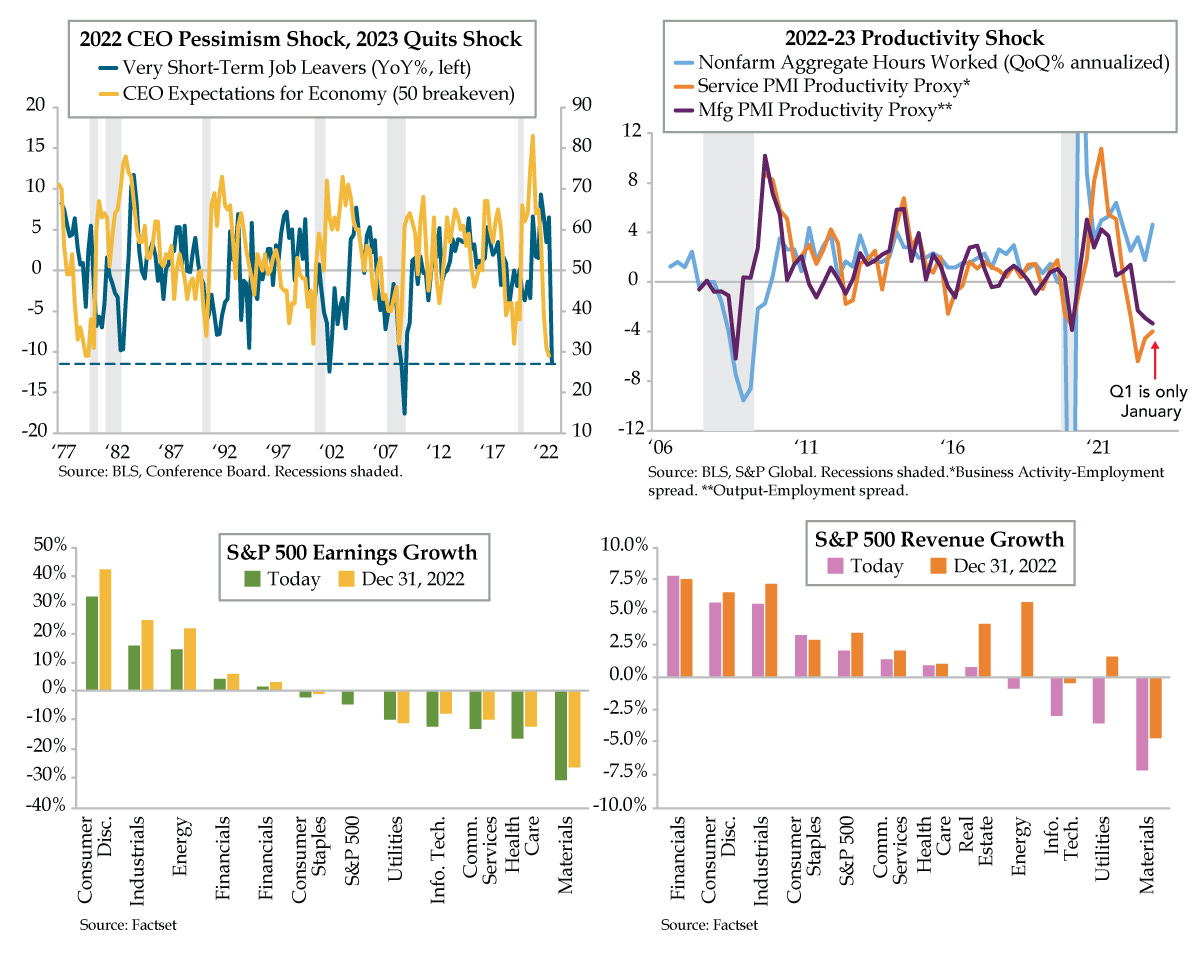

Two series within the January employment report added to the shock value. Our gauge for forward wage guidance tracks “good unemployment.” Very short-term job leavers, the percentage of unemployed who’ve voluntarily left their jobs and are out of work for less than five weeks, lead wages. This buried statistic in the household survey has consistently predicted the wage and salary component of the Employment Cost Index. Intriguingly, the year-over-year (YoY) trend in this metric (blue line) also has tracked – and even lagged – the path of CEO expectations (yellow line). From 2021’s second quarter to 2022’s final three months, CEOs flipped from all-time optimists to record pessimists sending expectations down 54 points, a scale and speed of without precedent.

Job leavers jump ship for better paying opportunities which leads us to ask: “Why did their money grab come to a screeching halt in January?” For starters, it’s clear the opportunities have dried up. At a more fundamental level, they know their job security, bordering on bravado, has turned into job insecurity. Both factors flag wage disinflation, a reflection of CEOs’ increased efforts to cut costs, the biggest of which is labor.

A productivity shock is the kicker. This lower-frequency, quarterly figure can be observed on a higher-frequency, monthly basis via S&P Global’s Purchasing Managers Indexes (PMI), which query C-suite occupants at companies of all sizes. The productivity proxy embedded in PMIs is the output/business activity-to-employment spread. Think revenues versus labor costs. The manufacturing proxy (purple line) fell to -3.3 in January, in line with Great Recession levels. The service proxy counterpart (orange line) remained below the zero line, at -4.0 in January, setting up the fourth straight quarterly compression.

Furthermore, aggregate hours worked (jobs times hours), the denominator in any productivity calculation, already stands 4.6% above the fourth quarter on an annualized basis (light blue line). Hours worked has been used as a guide for growth in the past since it is the labor input into an output estimation. However, when consensus first-quarter GDP (output) growth is projected at 0.1%, the back-of-the-envelope productivity forecast for the winter quarter is -4.5%. (Spank!)

To brass-tack it, productivity shocks are bad for corporate earnings because they expose companies to deleterious margin compression from high labor cost inflation. Should our guesstimate for first-quarter productivity prove accurate, U.S. nonfarm productivity will have contracted for five consecutive quarters on a YoY basis. There is no precedent for such an event.

According to FactSet, fourth-quarter S&P 500 earnings growth have been revised down from a -3.3% decline at year-end 2022 to a -5.3% drop as of last week. The bigger news was that first-quarter earnings are now set to drop -4.2% (green bar) after expectations for a flat quarter about five weeks ago. Every S&P 500 sector was revised lower, save for utilities. The first quarter going from a stabilization to a contraction raises the volume on a 2023 earnings recession.

The bigger story, in our view, is S&P 500 revenue growth expectations. On December 31, the fourth and first quarters were projected to expand by 3.9% and 3.4%, respectively. Through last week, the fourth quarter was upped to 4.3%, but the first quarter was cut to 2.0%. Nine of eleven S&P 500 sectors were reduced; only financials and consumer staples were not. Revenue expectations getting close to stall speed raise the risk for a full-blown recession. And here’s the kicker on the kicker: Second quarter revenues are penciled in at -0.1% -- that minus sign is not a typo. The unfolding productivity shock suggests you fade the fade in recession risk. CEOs still have more labor costs to cut.