Poison Ivey

The Coasters, a Los Angeles-based rhythm and blues/rock and roll/doo-wop, four-man vocal group from Los Angeles, struck gold in 1959. The groups first, second and third Top 10 Billboard hits that year were “Charlie Brown,” “Along Came Jones,” and “Poison Ivy.” The last of those resonates with us today, a track about a beautiful, but dangerous femme fatale that, like poison ivy, gets under your skin. Some 50 years later, the record was set straight. In 2009, songwriter Jerry Leiber revealed in Hound Dog: The Leiber & Stoller Autobiography that “Poison Ivy” was a metaphor for a sexually transmitted disease. Living up to its creation, the song was incredibly infectious in one form. Many artists recorded the tune including The Rolling Stones, Manfred Mann, The Romantics, Hanson, and Meshell Ndegeocello, with slightly altered lyrics. Her cover was included on the 1997 movie soundtrack for Batman & Robin, where Uma Thurman played the villainess…Poison Ivy.

Another ilk of poison was on display in Canada last Friday. The Ivey Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) had the floor pulled out from under it, falling to 33.4 in December from 51.4 in November. The 18.0-point drop was the largest non-pandemic single-month collapse on record and third lowest print ever. The four months of readings between 40 and 45 echoes only the shocks of the Great Recession and 9/11. The current episode was not induced by a forced shutdown or terrorist attack. On a fundamental level, thus, it’s worse than the Great Financial Crisis.

For perspective, the Ivey PMI is different than the metrics published by the Institute for Supply Management (ISM). The headline index is based on end of month data, covers the complete Canadian economy (including both public and private sectors), and is based on one sole question: “Are your purchases (in Canadian dollars) higher, the same, or lower than the previous month?” ISM does not include a question about purchases. In fact, the closest proxy is S&P Global’s quantity of purchases index for manufacturing. The Canadian version of this index (47.0 in December) has non-pandemic rivals back in 2015 when the oil bust collided with the industrial recession.

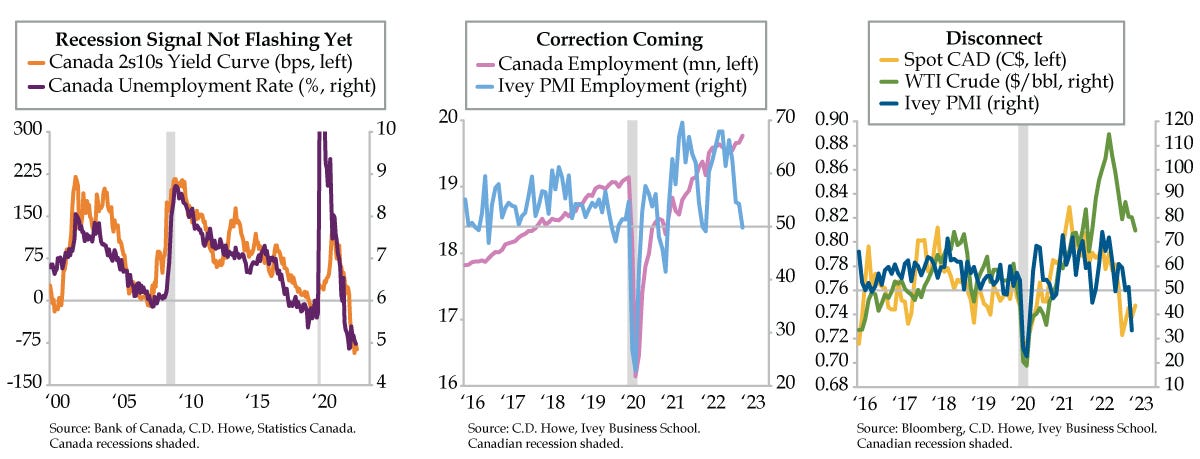

Last Friday’s Ivey bust was overshadowed by Canada’s employment report that blew the consensus out of the ballpark. As opposed to the meager 5,000 forecast, employment rose 104,000. Moreover, and in contrast to the anemic showing south of the border, full-timers accounted for 84,500 of the advance. Punctuating the rude gain, at 111,500, the private sector’s contribution dwarfed the headline gain. The incremental good news did not stop there. As opposed to the consensus’ expected one-tenth increase to 5.2%, the unemployment rate fell two tenths to 5.0% (purple line). Aggregate hours worked has registered three straight monthly gains, the most since 2021. That translated into a 1.7% quarter-over-quarter annualized fourth-quarter bounce following a stalling out in the third quarter. That’s a nice showing for an economy not renowned for its productivity track record.

The unexpected unemployment rate decline sustained a rally that got underway after August’s sharp 0.5 percentage point surprise spike. The four-month improvement kept end-of-cycle concerns at bay and bolstered expectations for a soft landing that defied the 65% recession probability over the next year reflected in Bloomberg’s December survey of Canadian economists. As is the case in all economies, the Canadian yield curve provides a recession backcheck. Monday’s -86 basis point inversion in the two-year/ten-year spread puts it closer to the -93-basis point nadir reached last November (orange line).

We don’t deny that nearly a quarter of a million jobs – 243,500 to be exact – were added in the four months ended December (pink line). But we think the good news ends there. Whole-economy guidance from the Ivey survey points to a stalling in the labor gains -- its employment index slipped to 49.8 in December. Not only does this follow 10 straight months of expansion through November, but the dip into contraction also has a sturdy precedential track record. Since 2019, the five other setbacks in the Ivey employment gauge have accompanied Canadian recessions.

At the risk of being alarmist, the next downshift in jobs might have more staying power vis-à-vis its predecessors. The collapse in the headline Ivey PMI flags a bevy of Canadian firms abruptly shrinking purchases at year-end. The likelihood of a protracted inventory correction in Canada has risen noticeably. As the global industrial supply chain loosened up in 2022, the impetus to stock-build took hold. In 2022’s second and third quarters, business investment in inventories registered respective readings of C$55 billion and C$57 billion. The C$112 billion cumulative increase was the largest two-quarter build in absolute terms on record.

Knowing what’s to come for Canada’s economy and documenting the ultimate damage may as well be in parallel universes. Canada’s fourth-quarter GDP figures are due out February 28; first-quarter data hit May 31. That leaves the exchange rate as the sole interim expression. Helpfully, the Ivey PMI (blue line) and Spot Canada (CAD, yellow line) have been more closely attuned to each other in the last 12 months. Using an even more real-time metric, while Monday’s release of the weekly Nanos Canadian Confidence Index delivered an inching up to 45.87 from 45.63 the prior week, expectations tumbled from +0.3% in the week ended December 30th to -0.2% in that ended January 6th. Given what oil is broadcasting, today’s employment green shoots might be better viewed as poison ivy.